Fundamentals of Phonetics: A Practical Guide for Students ― Article Plan

This comprehensive guide explores the science of speech sounds‚ offering students a foundational understanding and practical skills for phonetic analysis․

Phonetics is the study of speech sounds – how they are articulated‚ transmitted‚ and perceived; It’s a crucial field for anyone involved with language‚ from linguists and speech-language pathologists to actors and singers․ This isn’t simply about what sounds are made‚ but how they are made‚ the physical properties of those sounds‚ and how our brains interpret them․

Understanding phonetics unlocks a deeper appreciation for the nuances of language and communication․ It provides a scientific framework for analyzing and describing speech‚ moving beyond intuitive notions to precise observations․ This guide will equip you with the tools to dissect speech into its component sounds‚ recognizing variations and patterns․

We will journey through the core principles‚ practical applications‚ and essential resources needed to navigate the fascinating world of speech sounds effectively and confidently․

What is Phonetics and Why Study It?

Phonetics‚ at its core‚ is the systematic study of speech sounds․ It investigates how humans produce these sounds (articulation)‚ how they travel through the air (acoustics)‚ and how our ears perceive them (auditory processing)․ It’s a science grounded in observation and analysis‚ moving beyond simply hearing sounds to understanding their physical and perceptual properties․

Why is this important? Studying phonetics is vital for numerous fields․ Linguists use it to understand language structure and change․ Speech-language pathologists rely on it to diagnose and treat speech disorders․ Actors and singers utilize it to refine their pronunciation and vocal techniques․ Even fields like forensic science benefit from phonetic analysis in voice identification․

Ultimately‚ phonetics provides a key to unlocking the complexities of human communication․

Branches of Phonetics

Phonetics isn’t a monolithic field; it’s comprised of three primary‚ interconnected branches‚ each focusing on a different aspect of speech sound․ Articulatory phonetics examines how speech sounds are produced by the vocal organs – the tongue‚ lips‚ teeth‚ and so on․ It’s about the movements and configurations involved in creating sounds․

Acoustic phonetics shifts the focus to the physical properties of speech sounds themselves․ It analyzes the sound waves – their frequency‚ amplitude‚ and duration – using instruments like spectrograms․ This branch deals with the measurable‚ physical characteristics of sound․

Finally‚ auditory phonetics investigates how we perceive these sounds; It explores the mechanisms of hearing and how the brain interprets acoustic signals as meaningful speech․ These branches work together to provide a complete picture of speech․

Articulatory Phonetics

Articulatory phonetics delves into the mechanics of speech production‚ focusing on the articulators – the parts of the vocal tract used to create sounds․ These include the lips‚ teeth‚ alveolar ridge‚ tongue‚ hard palate‚ soft palate (velum)‚ and glottis․ Understanding how these articulators interact is crucial․

We describe sounds based on three key features: place of articulation (where in the vocal tract the sound is made)‚ manner of articulation (how the airflow is modified)‚ and voicing (whether the vocal cords vibrate)․

By meticulously observing and analyzing these features‚ we can categorize and differentiate between various speech sounds․ This branch provides the foundation for understanding how humans physically produce the sounds of language‚ forming the basis for accurate transcription and analysis․

Acoustic Phonetics

Acoustic phonetics investigates the physical properties of speech sounds as they travel through the air; It’s the scientific study of speech waveforms‚ analyzing characteristics like frequency‚ amplitude‚ and duration․ Specialized tools‚ such as spectrograms‚ visually represent these acoustic features‚ allowing for detailed examination․

Key concepts include frequency‚ which correlates with pitch (how high or low a sound is)‚ and amplitude‚ which relates to loudness or intensity․ Duration refers to the length of a sound․ These measurable properties provide objective data about speech․

Analyzing these acoustic signals allows us to understand how different sounds are perceived and distinguished‚ bridging the gap between articulation and perception․

Auditory Phonetics

Auditory phonetics focuses on how the human ear perceives speech sounds․ It delves into the physiological and neurological processes involved in hearing and interpreting acoustic signals․ This branch explores how the ear transforms sound waves into neural impulses that the brain then decodes as recognizable speech․

Researchers in auditory phonetics investigate topics like categorical perception – our tendency to hear sounds as belonging to distinct categories‚ even with acoustic variations․ They also study masking‚ where one sound interferes with the perception of another․

Understanding auditory processes is crucial for explaining why certain speech sounds are easily confused and how hearing impairments affect speech understanding․

The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA)

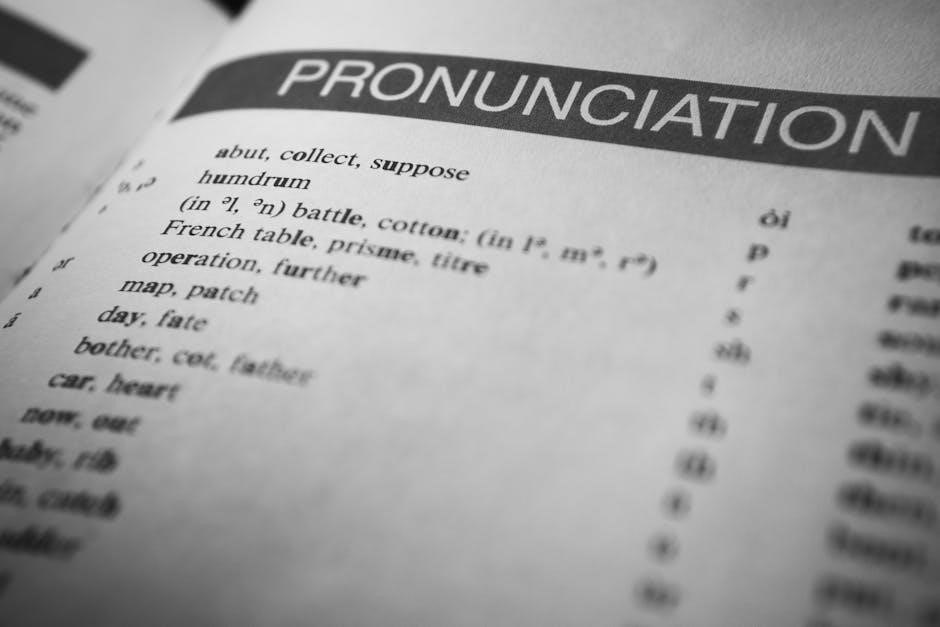

The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) is a standardized system for representing speech sounds․ Developed by the International Phonetic Association‚ it provides a unique symbol for each distinct sound‚ regardless of the language it’s found in․ Unlike ordinary spelling‚ which can be inconsistent and vary across languages‚ the IPA offers a one-to-one correspondence between sound and symbol․

This alphabet utilizes a combination of letters‚ diacritics (small marks added to letters)‚ and symbols to capture the nuances of human speech․ It’s essential for phoneticians‚ linguists‚ speech therapists‚ and actors who need a precise way to record and analyze pronunciation․

Mastering the IPA is fundamental to accurately transcribing and understanding speech sounds․

Why Use the IPA?

Employing the IPA transcends the limitations of conventional orthography․ Standard spelling systems are often ambiguous; for instance‚ the letter ‘a’ represents vastly different sounds in “father” and “cat․” The IPA eliminates this ambiguity‚ providing a consistent and universally recognized representation of each speech sound․

This precision is crucial for accurate phonetic transcription‚ allowing researchers to compare sounds across languages objectively․ It’s invaluable for language learners seeking to perfect pronunciation‚ and for speech-language pathologists diagnosing and treating speech disorders․

Furthermore‚ the IPA facilitates clear communication amongst professionals in fields related to speech and language‚ fostering a shared understanding of auditory phenomena․

Consonant Chart Overview

The consonant chart is a visual organization of all possible consonant sounds‚ categorized by place of articulation – where in the vocal tract the sound is produced – and manner of articulation – how the airflow is constricted․

Places range from bilabial (using both lips) to glottal (using the vocal folds)․ Manners include stops (complete closure)‚ fricatives (narrow constriction causing turbulence)‚ and nasals (air through the nose)․

Each cell represents a unique consonant‚ often with minimal pairs demonstrating the distinction․ The chart also indicates voicing – whether the vocal folds vibrate during production․ Mastering the chart is fundamental to identifying and producing consonants accurately․

Vowel Chart Overview

The vowel chart‚ typically a quadrilateral‚ represents vowel sounds based on tongue height (high‚ mid‚ low) and backness (front‚ central‚ back)․ Unlike consonants‚ vowels are defined by the shape of the vocal tract‚ not constrictions․

The chart’s corners represent extreme vowel positions: [i] (high front)‚ [u] (high back)‚ [æ] (low front)‚ and [ɑ] (low back)․ Vowels in between these points vary in height and backness․ Rounding (lip protrusion) is also indicated․

Understanding the vowel chart allows for precise vowel identification and production․ It’s crucial to remember that vowel space varies across languages‚ and the chart provides a relative‚ not absolute‚ representation․

Articulatory Phonetics: Speech Production

Articulatory phonetics focuses on how speech sounds are made․ Speech production involves a complex interplay of articulators – the lips‚ teeth‚ tongue‚ alveolar ridge‚ palate‚ velum‚ and glottis․ Air is exhaled from the lungs‚ initiating the process․

This airflow is modified as it passes through the vocal tract․ The tongue’s position is paramount‚ determining vowel quality and consonant manner․ The lips and teeth contribute to sounds like [f] and [v]․ The velum controls airflow through the nose‚ differentiating nasal from oral sounds․

Understanding these articulatory processes is fundamental to accurately describing and transcribing speech sounds․ It’s the basis for analyzing pronunciation and identifying phonetic features․

Place of Articulation

Place of articulation refers to where in the vocal tract a constriction occurs during speech sound production․ These locations are categorized based on the articulators involved․ Key places include bilabial (using both lips)‚ labiodental (lower lip and upper teeth)‚ dental (tongue tip and teeth)‚ and alveolar (tongue tip and alveolar ridge)․

Further along‚ we have post-alveolar (tongue blade and area behind the ridge)‚ palatal (tongue body and hard palate)‚ velar (tongue body and soft palate – velum)‚ and glottal (vocal folds)․ Identifying the place of articulation is crucial for distinguishing between different consonant sounds․

For example‚ [p] is bilabial‚ while [s] is alveolar․ Mastering these locations is essential for accurate phonetic transcription․

Bilabial Sounds

Bilabial sounds are produced using both lips as articulators․ These sounds involve a closure or narrowing at the point where the upper and lower lips meet․ A core set of sounds fall into this category‚ including the stops [p] and [b]‚ as in “pat” and “bat”‚ and the nasal [m]‚ as in “mat”․

The rounded vowel [w] also involves significant lip rounding‚ though it’s not a consonant․ Notice the difference in voicing: [p] is voiceless‚ while [b] is voiced․ Practicing these sounds requires conscious control of lip movement and airflow․

Consider how lip shape changes when producing each sound․ Bilabial sounds are among the earliest sounds children acquire‚ making them fundamental to speech development․

Alveolar Sounds

Alveolar sounds are articulated with the tongue positioned near the alveolar ridge – the bumpy area just behind your upper teeth․ This location makes them incredibly common across languages․ Key alveolar consonants include stops like [t] and [d]‚ as in “top” and “dog”‚ and fricatives such as [s] and [z]‚ found in “sun” and “zoo”․

The nasal [n]‚ as in “no”‚ is also alveolar․ Like bilabials‚ voicing distinguishes some pairs: [t] is voiceless‚ [d] is voiced․ The tongue tip’s precise placement – whether it’s a tap‚ flap‚ or full closure – influences the sound produced․

Practicing alveolar sounds involves focusing on tongue tip control and airflow direction․ These sounds are crucial for clear articulation and are often targets in speech therapy․

Velar Sounds

Velar sounds are produced with the back of the tongue making contact with the velum‚ or soft palate․ These sounds often have a deeper‚ more resonant quality than alveolar or bilabial sounds․ Common velar consonants include the stops [k] and [ɡ]‚ as heard in “cat” and “go”․ The fricative [x]‚ as in the Scottish “loch”‚ is also velar‚ though less frequent in English․

The velar nasal [ŋ]‚ found in words like “sing”‚ is unique as it doesn’t have a direct voiceless counterpart in English․ Voicing‚ again‚ plays a role in distinguishing [k] from [ɡ]․ Precise tongue-back positioning is key to accurate production․

Exercises for velar sounds focus on raising the tongue’s back and controlling airflow․ Mastering these sounds is vital for clear pronunciation․

Manner of Articulation

Manner of articulation describes how the airstream is modified as it passes through the vocal tract․ This dimension is crucial for differentiating consonants․ Sounds can be categorized based on the degree of closure or obstruction created․ Major manners include stops (complete closure)‚ fricatives (narrow constriction creating turbulence)‚ affricates (stop followed by a fricative)‚ nasals (air escapes through the nose)‚ and approximants (minimal constriction)․

Understanding these manners allows us to move beyond simply knowing where a sound is made (place of articulation) to understanding how it’s made․ For example‚ both [p] and [b] are bilabial‚ but differ in manner – [p] is a voiceless stop‚ while [b] is a voiced stop․

Practicing identifying these manners is key to accurate phonetic transcription․

Stops/Plosives

Stops‚ also known as plosives‚ are consonants produced with a complete closure of the vocal tract at some point․ This closure builds up air pressure‚ which is then released explosively‚ creating a noticeable ‘plosive’ sound․ English examples include [p]‚ [b]‚ [t]‚ [d]‚ [k]‚ and [ɡ]․

These sounds are categorized by their place of articulation – bilabial ([p]‚ [b])‚ alveolar ([t]‚ [d])‚ and velar ([k]‚ [ɡ])․ Voicing also differentiates them; [p]‚ [t]‚ and [k] are voiceless‚ while [b]‚ [d]‚ and [ɡ] are voiced․

The three phases of stop production are: closure (build-up of pressure)‚ hold (pressure maintained)‚ and release (explosive burst)․ Recognizing these phases aids in accurate perception and production․

Fricatives

Fricatives are consonants produced by forcing air through a narrow channel‚ creating turbulent airflow and a characteristic ‘hissing’ sound․ This constriction doesn’t result in a complete closure like stops․ Common English fricatives include [f]‚ [v]‚ [θ] (as in “thin”)‚ [ð] (as in “this”)‚ [s]‚ [z]‚ [ʃ] (as in “ship”)‚ and [ʒ] (as in “measure”)․

They are categorized by place of articulation – labiodental ([f]‚ [v])‚ dental ([θ]‚ [ð])‚ alveolar ([s]‚ [z])‚ and postalveolar ([ʃ]‚ [ʒ])․ Voicing distinguishes pairs like [f] and [v]‚ or [s] and [z]․

The degree of constriction and the shape of the vocal tract influence the specific sound quality of each fricative․ Careful listening reveals subtle differences between them․

Affricates

Affricates are unique consonants that combine the articulatory features of both stops and fricatives․ They begin with a complete closure‚ similar to a stop‚ but release into a fricative․ This creates a sound that starts with a ‘popping’ or ‘stopping’ quality and transitions into a ‘hissing’ sound․

English has two common affricates: [tʃ] (as in “church”) and [dʒ] (as in “judge”)․ Both are postalveolar‚ meaning they are produced with the tongue near the postalveolar region of the roof of the mouth․

Voicing distinguishes [tʃ] (voiceless) from [dʒ] (voiced)․ Recognizing affricates requires careful attention to the sequential nature of their articulation – the stop release into the fricative․

Voicing

Voicing is a crucial characteristic in distinguishing many consonants․ It refers to the vibration of the vocal folds during sound production․ Sounds produced with vocal fold vibration are termed ‘voiced’‚ while those produced without vibration are ‘voiceless’․

To feel the difference‚ place your fingers on your throat and produce the sounds [z] (voiced) and [s] (voiceless)․ You should feel a vibration with [z] but not with [s]․ This vibration is the key indicator of voicing․

Minimal pairs‚ like “pat” [pæt] and “bat” [bæt]‚ demonstrate how voicing can change the meaning of a word․ Mastering the identification of voicing is fundamental to accurate phonetic transcription and perception․

Acoustic Phonetics: The Physical Properties of Sound

Acoustic phonetics investigates the physical properties of speech sounds as they travel through the air․ These properties – frequency‚ amplitude‚ and duration – are measurable and provide objective data about speech signals․ Understanding these characteristics is vital for analyzing and synthesizing speech․

Sound waves‚ at their core‚ are variations in air pressure․ Frequency determines pitch; faster vibrations equate to higher pitches․ Amplitude relates to loudness; greater air pressure changes result in louder sounds․ Finally‚ duration refers to the length of a sound‚ influencing how we perceive it․

Specialized tools like spectrograms visually represent these properties‚ allowing phoneticians to analyze speech in detail․

Frequency and Pitch

Frequency‚ measured in Hertz (Hz)‚ represents the number of sound wave cycles per second․ It’s a fundamental physical property directly correlated with our perception of pitch – how “high” or “low” a sound seems․ Higher frequencies are perceived as higher pitches‚ and lower frequencies as lower pitches․

The human vocal range typically spans frequencies from around 85 Hz to 255 Hz for males and 165 Hz to 340 Hz for females‚ though these ranges vary considerably․ Variations in vocal fold vibration speed create these different frequencies․

Perceptually‚ pitch isn’t solely determined by frequency; psychological factors also play a role․ However‚ acoustic analysis relies on precise frequency measurements to understand intonation and tonal languages․

Amplitude and Loudness

Amplitude refers to the size or intensity of a sound wave‚ typically measured in decibels (dB)․ It corresponds to the amount of energy in the sound wave․ Crucially‚ amplitude is physically distinct from loudness‚ though closely related․

Loudness is the perception of sound intensity‚ and is subjective․ While a larger amplitude generally results in a louder perceived sound‚ our ears don’t perceive amplitude linearly․ A tenfold increase in acoustic power only corresponds to a 10dB increase in perceived loudness․

Factors like frequency also influence loudness perception; we are more sensitive to certain frequencies than others․ In speech‚ amplitude variations contribute to stress and emphasis․

Duration and Length

Duration‚ in acoustic phonetics‚ refers to the measurable time a sound persists․ It’s a physical property‚ objectively measured in milliseconds (ms)․ However‚ length is the perceived duration of a sound – a psychophysical phenomenon․

While closely linked‚ duration and length aren’t identical․ Our perception of length can be influenced by factors like surrounding sounds and the intensity of the sound itself․ A louder sound might seem longer‚ even if its measured duration is the same․

In speech‚ vowel length is particularly significant‚ often distinguishing between different vowel qualities or indicating emphasis․ Consonant duration can also signal phonetic boundaries and contribute to rhythmic patterns․

Auditory Phonetics: How We Perceive Speech

Auditory phonetics investigates how the human ear receives‚ processes‚ and ultimately perceives speech sounds․ It bridges the gap between the physical properties of sound (studied in acoustic phonetics) and our subjective experience of hearing․

This field explores the complex mechanisms within the ear – from the eardrum’s vibrations to the neural signals sent to the brain․ It examines how we categorize sounds‚ distinguish between phonemes‚ and interpret speech in various contexts․

Factors like background noise‚ individual hearing abilities‚ and even cognitive expectations influence speech perception․ Auditory phonetics also delves into perceptual illusions and the challenges of understanding speech in adverse listening conditions․

Phonetic Transcription: A Practical Skill

Phonetic transcription is the cornerstone of phonetic analysis‚ representing speech sounds with a standardized system – the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA)․ It’s a vital skill for anyone studying speech‚ linguistics‚ or related fields․

Transcription moves beyond orthography (conventional spelling) to capture the precise sounds produced‚ acknowledging variations and nuances often missed in written language․ This allows for accurate documentation and comparison of speech across different speakers and languages․

Mastering transcription requires careful listening‚ sound discrimination‚ and familiarity with the IPA symbols․ It’s not merely about writing down what you think you hear‚ but objectively representing the acoustic reality of speech․ Practice is key to developing fluency and accuracy in this essential skill․

Broad vs․ Narrow Transcription

Phonetic transcription exists on a spectrum‚ primarily categorized as broad and narrow․ Broad transcription focuses on capturing the most salient features of a sound‚ using a limited set of IPA symbols to represent phonemes – the basic units of sound that distinguish meaning․ It’s generally enclosed in slash marks / /․

Narrow transcription‚ conversely‚ aims for a much more detailed and precise representation‚ including allophonic variations (subtle differences in pronunciation) and phonetic details like aspiration‚ nasalization‚ or vowel length․ This is typically enclosed in square brackets [ ]․

The choice between broad and narrow transcription depends on the research question or analytical goal․ Broad transcription is useful for general phonetic analysis‚ while narrow transcription is crucial for detailed acoustic studies and capturing subtle phonetic nuances․

Common Transcription Challenges & Solutions

Phonetic transcription‚ while valuable‚ presents challenges․ Identifying subtle allophonic variations requires a trained ear and careful listening․ Dealing with regional accents demands familiarity with diverse pronunciations and avoiding imposing one’s own dialect․ Transcribing rapid speech can be difficult due to coarticulation – sounds blending together․

Solutions include consistent practice with audio examples‚ utilizing phonetic software for visualization (e․g․‚ Praat)‚ and consulting multiple sources for accurate IPA representation․ Focusing on acoustic cues‚ like formant frequencies‚ aids in precise vowel identification․ Slowed-down playback can help isolate individual sounds․ Collaboration with other transcribers provides valuable feedback and ensures consistency․

Resources for Further Study

Expanding your phonetic knowledge requires dedicated exploration beyond this guide․ Ladefoged & Johnson’s “A Course in Phonetics” remains a cornerstone textbook‚ offering detailed explanations and exercises․ The International Phonetic Association’s website (ipa4a․org) provides the official IPA chart and valuable resources․

Online platforms like YouTube host numerous tutorials on phonetic transcription and articulation․ Praat‚ a free software package‚ is essential for acoustic analysis․ University websites often offer lecture notes and phonetic databases․ Consider joining phonetics-focused online forums to connect with other learners and experts․ Regularly engaging with diverse speech samples – podcasts‚ interviews‚ and recordings – will hone your skills․